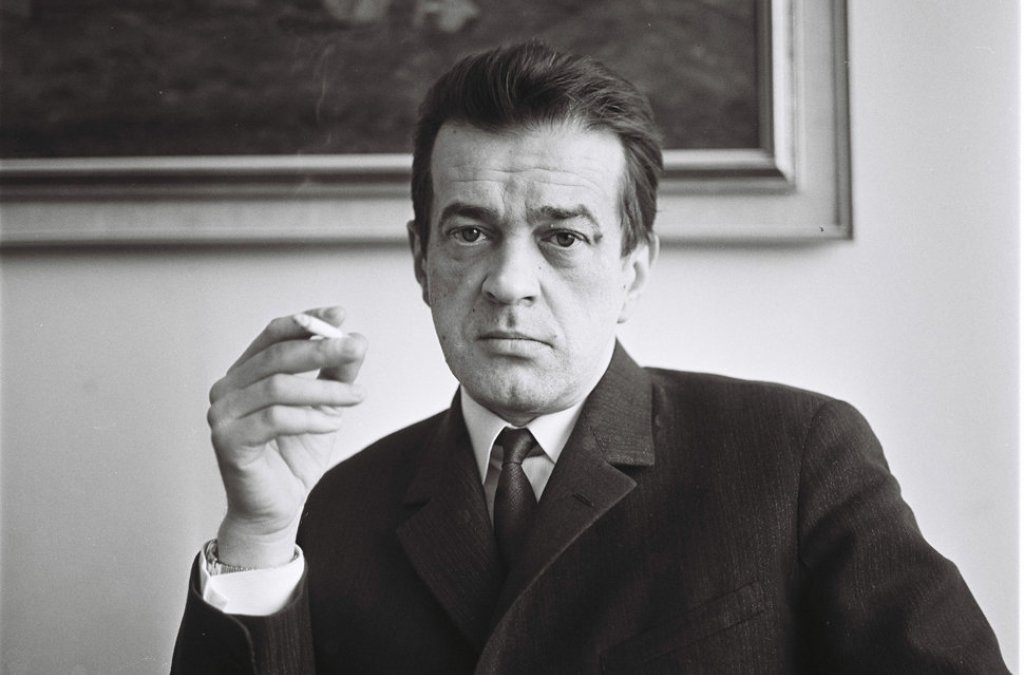

Sixteen years have lapsed since the death of Miroslav Válek. This poet was among the first who had crossed the Rubicon of schematic writing, and started writing modern literature. Several literary critics believe that he would deserve to be nominated, before Milan Rúfus, as the Slovak Nobel Prize laureate. He made a lasting and unmistakable impact, not only during his 19 years of service as Minister of Culture, but also on the way of thinking of the younger and the youngest generation of Slovak poets. “Young talents“, he used to say, “come with innocent and searching eyes, fighting on their own, fighting for literature – the kind of fight that must be fought time and again, because it never ends“.

In the late 1990s I was sitting with Jožo Urban in the Slovak Writers Club, talking about Miroslav Válek. It was a Robinson-like debate. For one, Urban’s debut in poetry was called Short Furious Robinson, and he wasn’t trying to conceal his warm feelings about Válek and his poetry. Sipping wine, we shared our reciting of a fragment from Válek‘s Robinson from the volume Attraction (Príťažlivosť) published in 1961: “And you had to start from scratch, / where man rises to his feet, / where a maiden-white flint, / sparkles in your hands, obscurely / and you’re falling to your face like a drunkard, / when you see, in stone and sand, / at the flash / of neon and candle light / the only solitary trace / of man“.

Válek as a man, was always in the presence of other people, and, at the same time a solitary Robinson. To celebrate his 70th birthday, a theatre play was produced on the themes of Válek’s life. It was written and directed by Roman Polák, who had borrowed a line from the poem Robinson: “I was looking for a ship that would be wrecked“, and the play was titled Robinson In Search of A Ship To Be Wrecked. Today, ten years later, I strongly believe that Válek was a Robinson, in search of a Robinson. He knew, from the beginning, that, figuratively speaking, his political ship was wreck-bound. Otherwise, he would not have criticized, in his poetry, the power, of which he was a part, the power that was so short-sighted as to be unable to accept criticism and have no idea of self-critique either. That appears, from today’s perspective, to be the purported meaning of his poems such as Killing Rabbits (Zabíjanie králikov) or Drumming On The Other Side (Bubnovanie na druhú stranu).

He was in search of and loved a solitary person, a person in the crowd who needs the energy locked in the poem, needs the power to be as good as his word and actions, the energy of what he has been through, as Válek believed, among other things, that energy is but a manifestation of matter, and so is poetry.

When you think of the juvenile Válek, what springs to mind is the image of a twenty-year-old poet who, on the 22nd of March 1947, at a joint meeting of Trnava’s schools, presented, as senior student of the Business Academy, his own novella entitled Saw How To Dance A Jitterboogie (Videl som tancovať Jitterbugie). The text has not been preserved, and we are left only to wonder as to its contents. We can but conjecture that the young Válek had a feeling for the rhythm of the boogie–woogie jazz style, characterized by a series of repetitions of the bass melodic structure, dancing to the rock-and-roll music.

Jitterbug is an energetic dance full of movement danced to a fast jazz or swing music, popular in the 1940s. Válek added the ie and used capital J. From that moment on, Jitterboogie became an obscure partner, perhaps the woman within, mother, daughter, mistress, wife, friend, but also Muse, Time or Death. Upon its author’s death, every poetical oeuvre resembles a Cabbala that, by linking and intertwining the verses, makes the world anew. The Jitterboogie simile provides one option of Válek’s inner story.

Since his early adulthood, Válek’s positions imply his interest in “drumming to the other side“. Drumming from within, from his substance, in the rhythm of swing and jazz, in the rhythm of the time he captured and analyzed and danced his Munch-like Lebenstanz.

In one interview he said: “Writing makes you, propels you to think of yourself as an intellectual problem. The answers are endless, but there is, essentially, only a handful of questions that we pose to ourselves“. One essential question he posed to himself is the question of man and his will, which is distinctly tackled in his most famous and most cited poem Home Is The Hands On Which You Can Weep (Domov sú ruky, na ktorých smieš plakať). In the poem, a history professor concludes that “History is made by the power of a personality, and the ensuing events only conform to the will of a genius“.

Through this solution of the will issue as one of the most fundamental questions of 19th and 20th century philosophy, Válek seems to join in on that streak of European thought framed by Schopenhauer‘s “Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung“. According to Schopenhauer, will is a metaphysical principle, providing the most fundamental instrument for explaining the world. Will is the deepest part of nature in every organic and inorganic creature; intellect is but secondary.

For Válek, the answer to the history issue was The Man of Personality, and to the will issue Man the Genius. He found man to be the measure of all things, setting in motion the events of his life, as well as the lives of others, if intercrossing them. Válek does not speak as Nietzsche does on the will to power as such, although the former had his share of such power. He speaks of will as of one form of energy that is capable of determining its manifestations both in one’s inner self and in the community-at-large – through word. Not by using power whose manifestations can be violent. Válek poetically encircles Nietzsche’s idea of man–personality, in which a fully-fledged human being observes the drives of his own self, not the standards of social morality.

The reality of arts and power, in which he was involved, partly with self-assured confidence and partly as a solitary long-distance runner, was his common battlefield. As he wrote in the poem “Game of Chess“: „...the game is often won by Knights, yet only the King can be check-mated“, he knew that forms only may succumb, not the inherent energy of a work.

Today, Válek is a true classic of Slovak literature. The onset of the new literary generation is associated with the journal Mladá tvorba (1956 – 1958), with Milan Ferko as the editor-in-chief and Miroslav Válek one of the editors. The foursome of poets: Ján Ondruš, Ján Stacho, Jozef Mihalkovič and Ľubomír Feldek (the only one born in Žilina) wanted to present as a “Trnava Group“ with its manifesto. However, fourteen pages of that text was discarded, under political pressure, shortly before publication, and their esthetic program was lost forever. Ľubomír Feldek has reconstructed the destinies of the “Trnava Group“ in his Homo scribens. One of the challenges of these Slovak lyrical poets was to be the “recovery of immediate sensual contact between man and reality“.

The story of the lost manifesto has an uncanny parallel with Válek‘s early lost novella Saw How To Dance A Jitterboogie. In the mystical arch, it seems to coincide with the true goal of the “Trnava Group“: to stop the growing loss of spiritual experience, a life lived “second-handedly“. To invite and treat the human being – the reader into one’s own experience, to be able to enjoy one deeper dimension of one’s own life. To love life and the world in the creeps of amazement.

Miroslav Válek has published eight volumes of poetry: Touching (Dotyky, 1959), Attraction (Príťažlivosť, 1961), Restlessness (Nepokoj, 1963), Making Love in a Goose Skin (Milovanie v husej koži, 1965), The Word (Slovo, 1976), From Water (Z vody, 1977), Forbidden Love (Zakázaná láska) and Picture Gallery (Obrazáreň). The names suggest his interest in the human being, in the authenticity of his/her relationships, but also his bitter testimony of his own belief. To engage in a deeply personal relationship is a gift that can hardly be given to oneself. That is the fundamental legacy of his poetry.

As he said on writing: “Every poet should feel the contours of his work in progress, not its specific form; this should be more of a prescience than a certainty, a feeling; in brief, the poet should feel the weighty presence of a certain sum of what has not been said as yet, to feel the size and weight of the future word (work) - and that about sums it up“.

Translated by Ľuben Urbánek