MILAN RICHTER: Without exaggeration you are one of the most experienced and longest „serving“ translators in Europe. You, indeed, started translating Czech (and even Slovak) contemporary poetry into German, your mother tongue, and publishing your translations when you were not even 20 years old. This happened over 70 years ago. Which authors, works, poetry did you consider the greatest challenge? And which of them was your greatest success?

EWALD OSERS: These are difficult questions. The greatest technical challenge was probably Vítĕzslav Nezval's Edison. Rhymed couplets, of course, have a long tradition in English poetry, thanks mainly to Alexander Pope, but Nezval manages to tell the entirely serious story of Thomas Edison with occasional tongue-in-cheek turns of phrase and a great many unexpected "fun rhymes" – and these had all to be rendered in English. To my own surprise, however, this proved easier than I had expected – or perhaps it was easier because I enjoyed the linguistic and prosodic challenge and the result was applauded by several competent judges. The greatest success were probably my translations of Jaroslav Seifert's late poetry. They not only earned me the European Poetry Translation Prize but, more importantly, played a major part in getting Seifert the Nobel Prize for Literature. Whereas I was attracted to Nezval by his linguistic brilliance and poetic fireworks, what attracted me to Seifert was his slightly nostalgic looking-back to his youth and his love of Prague. I have often thought that if I were a major poet, I would be writing poetry very much like Seifert's. My translations of Seifert's poems were frequently republished, sometimes as the "texts" to photographic works, and I owe most of my Czech awards to my Seifert translations.

MILAN RICHTER: Your encounter with Slovak poetry started in 1937 – Lukáč and Novomeský were well established poets then. Some 30 years later, after dozens of translations from Czech, German and Bulgarian, you returned to Slovak poets and became interested in Miroslav Válek’s poems. What did you find so fascinating in his verses, in his poetic world?

EWALD OSERS: I don't think I ever regarded Slovak poetry as a different world from Czech poetry. Few Czechs before World War Two knew – as distinct from understood – Slovak. But I had skied in the High Tatras as a teenager (I remember learning with some surprise that "to ski", in Czech "lyžovat" is in Slovak a reflexive verb, "lyžovať sa") and I had climbed there (with a guide) in the summer. And I suppose I am still a federalist at heart. Slovak literature was to me just part of the literature of Czechoslovakia. I think that Miroslav Válek, who was an admirer of the Czech poet Mikulášek, would have held a similar view. Anyway I met Válek and his poetry, it appealed to me and, with the encouragement of Peter Milčák, whose beautiful Modrý Peter publications I admired, I began to translate him. My volume The Ground beneath our Feet was first published in Slovakia, but it sufficiently impressed Neil Astley, the proprietor of Bloodaxe Books, to decide to bring it out again in England. I have since also translated Válek's poems for children – technically another challenge – but children's books with coloured pictures are expensive to produce and the publisher is still looking for a sponsor.

MILAN RICHTER: In the 1990s, after having introduced Seifert, Holub, and Nezval to English-speaking readers, you began translating poems by Milan Rúfus. It must have been a major challenge to transfer the specific Rúfus world with its traditional religious images into a much more sober language, a much more secular culture, wasn‘t it? How does Rúfus’s poetry appeal to British or American readers? Have you received some feed-back from them since the volume And That’ s the Truth was published with Bolchazy&Carducci Publishers last year?

EWALD OSERS: So far I have seen no reader or critical reaction to And That's the Truth, but there hasn't really been enough time. I don't think that Milan Rúfus's world is entirely strange to the Anglophone reader: there have been religious and symbolist poets even since Gerald Manley Hopkins. What worries me rather more is whether the fact that this is a bilingual publication – I am a firm believer that this is the best way of presenting translated poetry – might not scare off some readers, who might regard this as a "scholarly" publication. Time will tell. The fact is that success or failure of a "borderline" publication often depends on one single review in an influential publication. A good review in the Times Literary Supplement or the New York Review of Books would be enough to establish the book on the Anglo-American market.

MILAN RICHTER: Comparing the position of Czech or Bulgarian poetry in the editorial programmes of British and Irish publishers, comparing all those names, known and unknown to the English speaking (and reading) audience, with the few Slovak poetry books ever published in English (by Novomeský, Válek, Rúfus, Buzássy, Laučík) – what could be done more for the promotion of excellent Slovak poets, living and dead, such as those already mentioned, as well as Ján Smrek, Štefan Žáry, Ján Stacho, Ľubomír Feldek, Štefan Strážay, Mila Haugová, Ivan Štrpka, Ján Zambor, Ján Švantner, Dana Podracká, Anna Ondrejková, Viera Prokešová, and others, for the promotion of their poetry in the English-speaking world?

EWALD OSERS: Books are written by their authors, but bestsellers, and even midlist sellers, are made by their publishers. It all, unfortunately, comes down to money. My four volumes of Bulgarian poetry are not selling at all, they are not even borrowed from public libraries. Czech poetry is doing a little better – but even here it is not Seifert or Nezval that sells in appreciable numbers, but Miroslav Holub. As one of Holub's principal English translators I am naturally pleased about that – but I also realise the reason. Holub used to attend literary festivals, read his poetry (often together with me), he was amusing and funny when he gave interviews, a deliberate clown and he became a popular figure in the "performance poetry" world. So much so that in the USA he was paid $400 for a reading. In an ideal world, if Slovakia could afford to bring a poet over to England, if he (or she) could give public readings at half a dozen festivals and in a dozen bookshops, colleges and universities, if the Slovak embassy could host repeated presentations, inviting every literary critic to attend a generous buffet, not just canapés and one drink, if the embassy could persuade (and finance) a "Week of Slovak Literature" in one of the major chains of bookstores, if it could insert (and finance) articles on Slovak literature in the major daily papers, or at least the Sunday papers, it might become "fashionable" to buy a volume of Slovak poetry – but of course we are day-dreaming. And it would help if the woman poet was beautiful. In our real world we (I mean pOSERSple like me, I myself am near the end of my career) must just work away, inch by inch.

MILAN RICHTER: Recently, in October 2007, you were awarded the prestigious Hviezdoslav Prize in Bratislava. After many prizes, awards, medals and orders you have received for your translation and promotion of Czech, German, Bulgarian and Macedonian literatures in Great Britain, this is your first award from Slovakia. What does it mean to you, to a multilingual personality who after 70 years spent in England still fluently speaks Czech and even Slovak?

EWALD OSERS: Of course I am delighted that my work for Slovak literature has been rewarded by this prestigious prize. As for what you call my multilingualism, it is not the case that, after 70 years in England, I "still fluently speak Czech and even Slovak". The truth is that, as my old friends all assure me, I speak Czech better now than I did when I was living in Prague. This, of course, is due to my intensive contact with Czech writing and, more importantly, with Czech friends. For the past 30 years or more I have been visiting Prague regularly, at least twice a year. My Slovak, while quite good for a Czech, is very far from perfect, but if I have a lot of time I can probably write a letter or even an article in Slovak with not too many mistakes. Incidentally, it is my intention to bring out an English volume of poetry by a Slovak poet from your generation in the course of 2008.

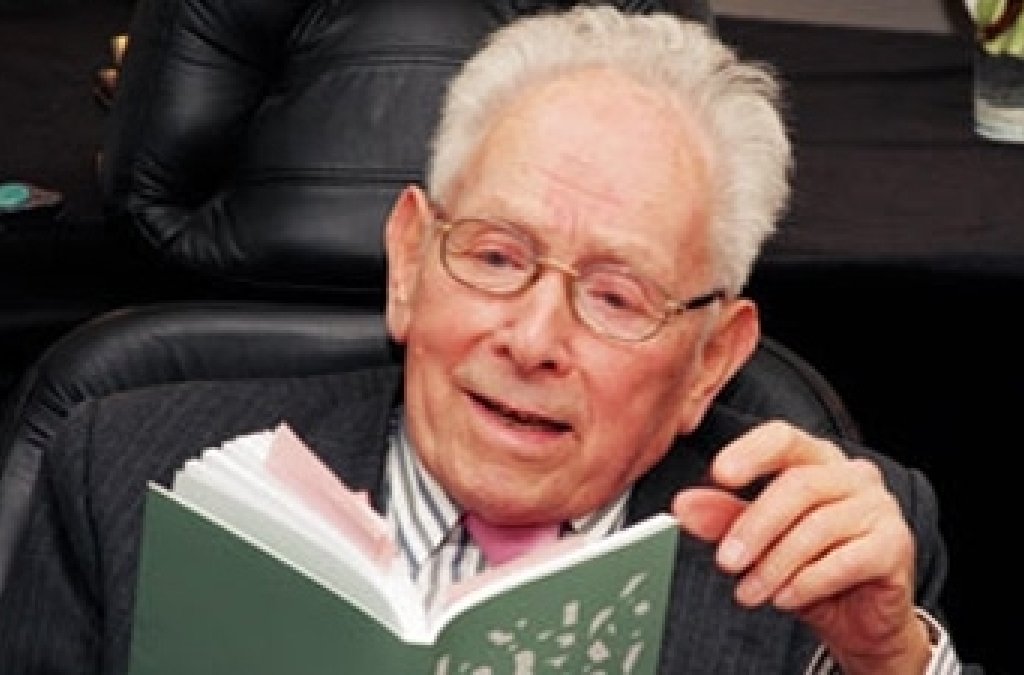

Ewald Osers was born in Prague in May 1917 in a secular Jewish family. He studied chemistry in Prague and in London where he stayed after the Munich Agreement, working with the BBC until his retirement in 1977. Osers started translating poetry as soon as in 1937, mostly into his mother tongue German. In the UK he continued with the translation work, since 1942 exclusively into his “host” language English. He translated dozens of non-fiction books from German, novels by Jiří Mucha, Arnošt Lustig, Ivan Klíma, Thomas Bernhard etc. but gradually became well-known for his poetry translations, first of all of Czech poets, such as Jaroslav Seifert, Vítězslav Nezval, Miroslav Holub, Jan Skácel but also of German poets (Rose Ausländer, Reiner Kunze, Hanns Cibulka and others), Bulgarian (Lubomir Levchev, Geo Milev and others) and Macedonian (Mateja Matevski), as well as poetry of the Silesian poet Ondra Lysohorsky. In the late 1980s Osers focused also on two major Slovak poets: Miroslav Válek (The Ground beneath our Feet, 1969) and Milan Rúfus (And That's the Truth, 2006 – together with Viera and James Sutherland-Smith). In the 1990s he published poems by Štefan Strážay, Milan Richter, Margita Dobrovičová and others in British and US literary magazines and in the Slovak Literary Review in Bratislava. Recently Osers translated the famous autobiographical novel by Alfréd Wetzler, one of the Slovak Jewish escapees from Auschwitz, What Dante Didn't See (under the title Escape from Hell) and two theatre plays on Kafka written by Milan Richter.

Ewald Osers published three volumes of his own poetry and a book of memoirs (The Snows of Yesteryears) which was translated also into Czech. He served as chairman of two British institutions (theTranslators Association and the Translators' Guild) in the 1970s and 1980s and he was vice-president of the FIT (International Federation of Translators) for two terms. For his translations of around 150 books and promotion of national literatures in the English speaking world he received more than 25 prizes and honours, e. g. the Schlegel-Tieck Prize 1971, the European Poetry Translation Prize 1987, the Order of Cyril and Methodius, Bulgaria, 1987, the Austrian Translation Prize 1989, the Officer's Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany 1991, the Macedonian Literature Award 1994, the Medal of Merit of the Czech Republic 1997, both Aurora Borealis Prizes (for fiction translation and for non-fiction translation) 2002, and the Pavol Országh Hviezdoslav Prize, Slovakia, 2007.