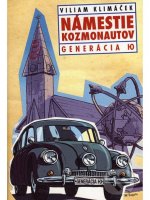

COSMONAUT SQUARE

Generation Ю[1]

(Extract)

WEDNESDAY, EARLY MORNING

Maroš kissed his sleeping wife and quietly slipped out of the bedroom. He was carrying his jeans and a T-shirt with a picture of ball-bearings, a symbol of the time not so long ago when he was still working in a factory called Achko. The ball-bearings cuddled up to each other tenderly and tried to convince the public that they were what Achko produced. The picture had grown pale with frequent washing, as its owner had with early rising, and the public had also long been aware that the abolished ball-bearings firm was in fact an arms factory.

Maroš dressed himself with habitual movements. His forty-five-year-old body managed it without unnecessary rustle, although more and more often a sharp pain drew his attention to his right shoulder, but this was already an everyday sensation. A little uncertainly he went down into the garage and took out his father's bicycle.

Until recently its massive frame and large wheels had been an object of ridicule. The seat had two springs capable of absorbing the shock of a railway wagon. The bright Cyrillic lettering on the frame read - ЗИФ. But now this Soviet means of transport had already moved into the veteran category and begun to evoke dreamy respect in some of its generation. Maroš Kujan wouldn't hear a word against his navy blue ZIF.

He pushed it out of the gate of the sleeping house and walked down the steep slope through the cemetery. At the stones of the grotto sheltering a plaster Virgin Mary in a niche in the rocks, he crossed himself perfunctorily. When he reached the dilapidated chapel, he mounted the creaking seat and let it carry him down the Road of the Cross.

He sped through the awakening town under his own momentum, but pedalled at least half way up the asphalt road leading under the viaduct and up a steep hill, away from the town – to a point level with the road sign VEĽKĚ ROJE, the limit of his fitness.

He dismounted and pushed his bicycle uphill, puffing as he went. He passed the metal gate with its welded D*R*E*V*O*Č*A*S sign, whose letters had once been separated by red stars, now only rusty. Only last month the company had employed him, but the coffee tables of pale walnut that always looked as if water had been spilled on them, or the mini-bars with protruding doors were so hideous, that not even their Belorussian partner would take them any longer. Maroš had been one of the first to be made redundant.

At the top of the hill he turned off onto a dirt road and hid his bicycle among the bushes. He opened the little leather bag behind the seat and took out a mirror, a brush and a tiny bottle of artificial blood, which made from ketchup, glycerine and food dyes.

First he changed his trousers for ones with a hole in the knee. Then he skilfully made himself up. The little mirror showed him a man with a cut over the eye and a bloodstained face. Maroš was satisfied. He sat astride his bicycle and waited at the edge of the dirt track.

The asphalt road was lined on either side with wild undergrowth and the turning off into the field was hardly visible. Well hidden among the leaves, he watched the traffic on the main road. Two rusty Skoda MBs, an Avia lorry carrying cement and an interminably slow tractor.

His heart was beating fast with excitement. He let several more cars pass until an itching in his back told him the time had come. As a matter of principle, he only picked out luxury makes. He could distinguish them by the sound they made.

A Czech Hyundai and a woman at the wheel. He made up his mind in a fraction of a second. He pushed off hard with his feet and came hurtling into the bend at precisely the same moment as the red car. The Hyundai's brakes squealed and Maroš instantly shot off into the bushes. The car didn't even touch him. A few scratches were added to the painted blood.

He lay under the fallen bicycle and waited. The car came to a halt. For a moment nothing happened. Guggling noises came from the exhaust.

Don't let her drive away like the one yesterday, he prayed to himself.

The car was put in reverse gear. Maroš let out a sigh of relief. The door opened and calves wearing red court shoes stepped out.

Matching the metallic paint, thought Maroš and groaned, "Help!"

"Are you all right?" the young woman cried out in Czech.

The well-oiled wheel of the ZIF spun impressively.

"Call…the police!" sighed Maroš, pulling himself to his feet with difficulty.

A look of horror appeared on the woman driver's face.

"For heaven's sake, I've got a new driving licence! Are you all right?" she asked anxiously.

"My head hurts," Maroš said, "and I've dislocated my knee."

He took a couple of steps and, with a painful grimace, leaned up against the purring car. "You were going terribly fast, miss. You'll lose your licence. Was it worth it? You could have killed me!"

The woman, already pale enough as it was, turned even paler.

Maroš added sadistically, "I've got a wife and child, but you obviously don't care, if you bloody well tear along at a hundred and ten!"

"We'll bandage it up…" the driver said in a shaky voice, pulling out an immaculate first-aid kit.

With trembling hands she unscrewed a bottle of tincture.

Maroš scornfully snatched the plastic box from her hands and hurriedly bandaged his knee. "The doctor will make me stay home for a week. I shall lose my job!"

"I'd pay you compensation," the woman reached into her handbag.

That was just what he had been waiting for. It was a moment worthy of organ music, when all the stops are pulled out and, to the thunder of pipes, from behind a cloud instead of God's son and the Holy Ghost the state's banknotes appear: Hlinka and Štefánik, with the signature of the governor of the national bank forming a filigree decoration around them.

Maroš blissfully half-closed his eyes.

"Here," the woman handed him quite different faces. "That's all I've got."

Maroš looked at the two one-hundred euro notes reminiscent of lottery tickets and recalled the previous day's exchange rate. Over eight thousand Slovak crowns! We-ell now… He took a deep breath and a fraction of a second later greedily stretched out his hand.

A look of doubt appeared on the woman's face, but the hooting of the cars heading at speed for the town forced her to get back into her shiny red car. However, it was possible to sense relief in her hurried steps. She slammed the door and took a last look in Maroš's direction. Just at the right moment his indestructible Soviet bicycle, the source of his livelihood, fell from his hands. He bent over with exaggerated difficulty.

The Hyundai started off and the warm breeze of that August morning dispersed its cloud of petrol fumes. The lead fallout gratefully settled on the little sour apples lining the branches of a gnarled apple tree. Years ago it had been planted at the edge of the road by some trusting man, perhaps a distant relative of Maroš, a happy man who in his lifetime had met more horses than four-cylinder engines.

The ground shook. Somewhere a long way off riveting hammers were stitching Europe together.

Standing out like motley patches on a velvet coat, the new countries of the Union tried to keep their dignity in the emerging alliance, whose only clearly visible ideal was the common market. Along with an unconvincingly declared solidarity of the more powerful with the weaker. The inhabitants of the patches were well aware that at first Old Europe would show the world only that side of the coat where their gaudy blotch could not be seen, and therefore did not get any more excited than usual.

Who knows whether this meant they had missed a historic moment for sincere joy at unification? Many sensed it, but swallowed the moment as they had done a thousand times before, for experience had taught them that with us or without us, the wheel of history keeps turning.

It is probable that few people believed there could be a repetition on the continent of Europe of the miracle of the melting pot, which centuries before had united the nations emigrating to the territory of North America into a compact formation of one body and one mind, thus creating the most maligned letters of the alphabet in history – the twenty-first, nineteenth and first – that is, the USA.

In spite of these doubts, it was, however, certain that nothing better could happen to little Slovakia than to be stitched onto another piece of Europe that had created such wonderful things as Saint Peter's Basilica, psychoanalysis and the film The Yellow Submarine. The further from the capital, the less did the shocks of the riveting machines make themselves felt in the everyday lives of the inhabitants.

And in the epicentre of our story, in the town of Veľké Roje with its population of seven thousand, the ground did not shake at all. The last event worthy of that name had taken place fifteen years earlier and remained recorded in the town chronicle as a moderate earthquake that had produced cracks in the asphalt pavement outside the nursery school in M.R.Štefánik Street necessitating repairs to the tune of 12,860 crowns and causing the tragic death of one citizen.

The fact that the citizen had died an unusual death, in that he had been swallowed up by a rift in the ground and his body had not yet been found, was not spread around unnecessarily. Nor that until of late he had been the most famous inhabitant we are going to hear about.

Why the town was called Veľké Roje – Great Swarm – no one has yet managed to explain. Bees had never been kept on a large scale and no reference to them has been found in any chronicle. The number of beehives in the gardens was no greater than the national average, but no one protested when on the town's newly designed coat-of-arms a bee appeared, sitting on a wooden spoon. The production of wooden spoons had a century-long tradition here, gradually moving from the isolated hillside cottages in the surroundings to the Drevočas company, which, with good intentions, had extended its assortment to include unsaleable furniture.

Veľké Roje was a town that history avoided.

The emperor's coach had passed through its streets but once and only thanks to a broken wheel can the town museum now pride itself on the bent metal of its tyres. The Turks didn't get this far, the Hussites avoided the valley and Hurban's followers didn't even stop to fill their flasks with water. In the First World War only ten men were recruited, of whom six returned and the town erected a monument to the remaining four – a marble soldier with a marble rifle, admired above all by the children, who were always trying to climb up onto the plinth and release the marble safety catch on his weapon.

Partisans had only fought in the neighbouring district, but fortunately they had also dug an underground bunker in the Veľké Roje area, so the village could declare itself an insurgent municipality, for which it later received a town charter. In August 1968 the Drevočas factory had been closed for the summer holiday, so it was the only company in the district that did not go on strike in protest against the invasion of the allied armies, which earned it the title of Company of the Order of the Red Star and it proudly welded on the red stars between the letters of its name. In 1989 only three young people from the town emigrated and no one ever heard of them again, so it is impossible to disprove the rumours they had joined the foreign legion that were divulged in the restaurant of the Horec Hotel after Fernet Stock and tonic.

The Velvet Revolution also passes without any slaps in the face and threats to members of the Communist Party, because every third inhabitant had been in that party ("For the children's sake!"), every other inhabitant had a member of the family in the party ("I'm not going against my brother, for God's sake!") and everyone had at least one good friend who was a communist ("do you know what he'd say over a beer?!"). The only real local dissident, Vlado Juráš, quietly returned from prison and built up an honest private business as a car mechanic.

Rising above the town was Javorové hill with its television transmitter and deep in the forests were the remains of a Soviet military base, which fortunately they had not had time to complete.

The town's days passed without quakes and tremors, the ground beneath it was firm until that Thursday…, but don't let's jump ahead, it is now only Wednesday, still fairly early, and Maroš is examining the one-hundred euro banknotes from all sides and feeling happy. The August air over the fields is warming up and the currents of air are lifting the flying nano-grains of pollen, sent whirling by the rustle of the banknotes, to dizzying heights.

One grain of pollen gets caught in the right current and the chimney of hot air carries it up steeply to where it mixes with the cold mass of wind and, having performed a mad pirouette, tentatively sets off in the direction of the town. From up there the pollen has a clear view of the geometrical purity of the streets, which fan out from the square lined with old houses and dominated by a strange building that from a height is reminiscent of a rocket prepared for launching, but the grain has no time to admire the town centre encircled at a respectful distance by satellite blocks of reinforced concrete flats, because the cool current carries it off to the opposite hill with its identical terraced houses with front gardens, two windows and gable roofs; it can already see in detail one with a washing line, on which a dark-haired woman is at that precise moment hanging out wet panties and the uncontrollable nano-grain with no nano-emotions whatsoever heads at full speed for the face of the woman, where it is sucked in at a terrible speed through the enormous opening of a nostril, to crash into the vibrating villi of the warm pink mucous membrane, which immediately connects with defensive mechanisms, sending the lungs an order to hold the breath, pull down the diaphragm and with a rush of air immediately drive the nano-intruder out from the body.

LATER WEDNESDAY MORNING

"Bless you," growled Mad Šani.

Milka wiped away the tears that had sprung to her eyes from the sneeze. She staggered a little, glancing unwittingly at the sun, and sneezed a second time.

This time Šani didn't bother to respond politely, but quickly disappeared in the direction of the back yard. He was hiding something awkwardly under his shirt. Milka hurriedly pegged out the rest of the washing and followed her father-in-law.

As a matter of principle, Šani Kujan, Maroš's father, used to improve things that no one needed and develop things no one had asked for. He was a Renaissance man capable of installing in the house a pneumatic message system driven by an ordinary vacuum cleaner, through which he would send orders to the children, but he was not willing to mend a hair dryer or sharpen a knife.

"Narrow horizon," is what he used to say.

Milka quickly glanced through the open window of the children's room. With his tongue stuck out in concentration, Peťko was fitting together red and yellow pieces of Lego. She ran round the house and tried the handle of the back gate. It was bolted.

"Open the gate, Dad!" Milka called. "I know you're there."

Instead of an answer, there came the sound of metal scratching metal. Šani was putting the finishing touches to one of his devices.

"Dad!" cried Milka in a louder voice.

The scratching speeded up considerably.

"If you don't open the gate, I'll break it down!" Milka shouted angrily.

The grating metal sound stopped. After a short pause it was heard again, this time with an even greater frequency. Milka knew she couldn't break down the gate.

"I'm going to get the axe!" she thundered.

The din of the work on metal was enriched by a quiet laugh. The gate was built in such a way that no one could get into Šani's polygon without his permission. Now a hissing sound was heard. Šani had let some gas out of a cylinder.

"You'll blow us all up! Me and the child!" Milka yelled hysterically.

Here and there the hissing of the gas drowned her voice. That maniac in his fortified garden was no doubt testing another of his inventions. The last device, a pocket flame gun for liquidating wasps' nests, which worked on the basis of processed petrol, which Šani had distilled, unaware that he had produced something like napalm, had been confiscated by the police after he had set fire to a wooden fence, next to which the unfortunate wasps had built a temporary home. As the secretary to the mayor of Veľké Roje lived on the other side of the fence, police intervention had been speedy, brutal and effective.

"Police state!" battered Šani had yelled.

In its report the patrol claimed that Šani had attacked them with the flame gun and here the testimony of two policemen against a single witness still had the power of the law. Now it was evident that he was determined not to interrupt his experiment, because his son's wife was on his land.

Milka took a step back, thinking that she would grab Peťko and their savings books, but then her fighting spirit returned.

"Dad?" she called out, seemingly calm, "if you don't open the gate, I'm going to stop your experiment in the washhouse."

The hissing of gas ceased. The sound of tools being put away could be heard and a moment later the metal gate was opened.

An angry Šani emerged. "Is it still going?!"

There was a dangerous glitter in his eyes.

Milka nodded. In the cellar, which in happier times had housed the washing machine, ironing board and juicer, there was now a cauldron with a stirrer, the handle of which kneaded day and night some kind of mixture, the purpose of which Šani had not disclosed to anyone. On paper the house belonged to her father-in-law and Milka Kujanová lived there with Maroš and Peťko only because there was no hope of getting a flat in Veľké Roje.

"I'll turn it off, if you don't show me what you're doing!" the young woman declared with determination.

By the way, many men were willing to agree that she was beautiful when she was angry. When the heavens created her, they had run out of every colour except black, but her dark hair and eyes gave her oval face a touch of the exotic. When you met her, you had the feeling she reminded you of someone, but you let it go. Apart from Maroš, who had realised long ago that his wife looked like the illustrations from the The Egyptian, one of the few books he had read right to the end. For this reason he loved her all the more.

"I'll turn it off!" Milka pressed him further.

"Narrow horizon," her father-in-law growled and stood aside.

In the middle of the small garden, well hidden from inquisitive eyes behind a metal fence, stood a rocket, about two metres high. It was connected by hoses to welding cylinders and Milka felt sick. A few moments and they could have all been blown up.

The tip of the rocket seemed to be surrounded by bottle openers. On the round ramp twenty centimetres in diameter something was moving. Milka bent over the fuselage with its orange lettering SOJUZ 333. Thrashing about in the cabin of the space ship was a Peruvian guinea pig, attached there by adhesive tape.

"You've stolen Habakuk?!" she shrieked in the voice of a Greek goddess.

She began to tear off his fetters, but the guinea pig was in a perfect trap.

"You'll kill us all!" she shouted.

The guinea pig, emboldened by the voice of its mistress, contributed at least its squeals to its liberation. Less than a quarter of an hour earlier it had been comfortably dozing in its cage, when the senile hands of the inventor had taken it out of the warmth and hidden it under his shirt.

"Last time you killed the gerbil!" Milka went on furiously.

The late rodent had fallen victim to an experiment in which he had unwillingly tested a centrifugal machine for astronauts, converted from a spin-dryer. The gerbil had not survived the acceleration stress of many G and Milka and Peťko had buried him in a chocolate box, wrapped up in aluminium foil.

"I took care this time!" objected Šani, offended.

Next to the torn adhesive tape there lay a pared carrot and half an apple, food for the future astronaut.

"If you don't care about us any more, Dad, at least don't take the boy's pets!" were Milka's final words.

SOJUZ 333 stood abandoned in the middle of the garden like a huge bottle of beer fated to weather for all time.

"Look, Habakuk's been for a walk," she lied to the child, putting the stressed guinea pig back in its cage.

It immediately crawled into its little kidney-shaped plastic house and stayed there for two whole days. Milka hurriedly dressed the boy and they stepped out into the yard.

"I'll just get the key from the shop," she told her son, going back into the room.

The part of the house in which they lived had, for obvious reasons, windows facing the street and not the garden of experiments.

It only took her a minute, but Peťko managed to run over to the half-open gate and his eyes lit up at the sight of his grandfather's rocket.

"Booooom!" said the little boy.

"Would you like to fly? One day I'll built you one like that," Šani told him in a whisper, because his mother was approaching with ominously tight lips.

"Come on!" she pulled her reluctant son away to take him to nursery school.

"Narrow horizon," the inventor summed up and returned to his spaceship ramp.

Not far away busy bees were collecting on their leg bristles nano-allergens from flowers, which by some mysterious process they would transform into popular honey.

Translated by Heather Trebatická

[1] Yu (Ю, ю) is a letter of the Cyrillic alphabet, used here by the author to symbolize the English homonym "you" with reference to this generation's unquestioning admiration for the lifestyle in the West.