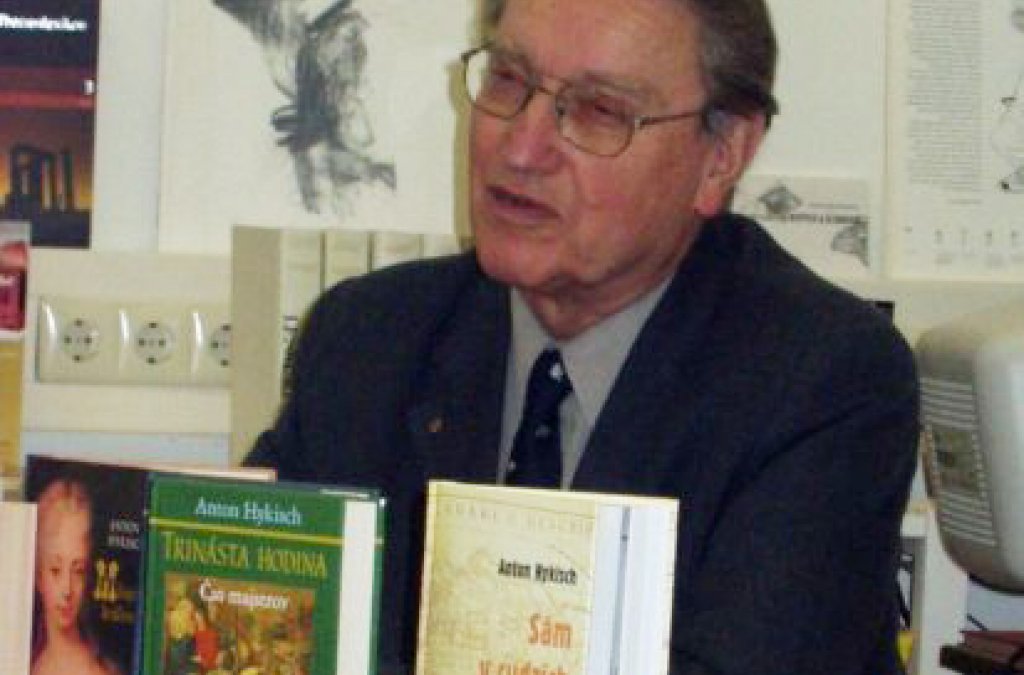

Anton Hykisch (born in 1932, in Banská Štiavnica) has a special standing in contemporary Slovak literature. Although novels are the focus of his work, he publishes collections of short stories, essays, news stories, non-fiction books and memoirs of his time spent in politics and diplomacy. His books have been translated into more than ten foreign languages, making him the most translated author in Slovakia. His historical novel Adore the Queen (Milujte kráľovnú, 1984) has met with such success in Germany that it was published twice in one decade, there. At this year’s Frankfurt Book Fair, together with his Austrian publisher Wieser, Hykisch introduced the German translation of another one of his historical novels, Time of the Masters (Čas majstrov 1977, 1983).

Since the introduction of this translation in Frankfurt happened very recently, we started our interview inquiring about the translation of his novels into German and other languages.

ANTON BALÁŽ: You have extensive experience with translation of your books into other languages and since you speak many of them (German, English, Polish, and Hungarian) you can evaluate their quality very well. Within the EU, Slovak is among the least widespread languages and so when translating from Slovak, the translator’s personality, knowledge of Slovak, approach to the text, and to the precision of the original text and so on, are crucial. Taking this into account, how do you rate the translations of your books, especially those published in German which include a lot about Central European life and institutions?

ANTON HYKISCH: I think I got lucky with translators. Time of the Masters which is set in the Middle Ages, requires the translator to know history, art techniques, and mining technology. The translators, of course, consulted with me and I had to clarify many things. The Hungarian ( by Oľga L. Gályová) and Russian translations were perfect. The Russian translation also featured a historical foreword of the Russian literary scholar Oleg Malevič. The German translation of the novel is the work of an Austrian diplomat in Slovakia, Johannes Eigner. It is dense and with some reductions it attempts to appeal to the contemporary German reader. He also added his own notes. Interesting is that the translators want to see the setting of the novel. I had to drive the Russian translator Nina Šulginová from Bratislava to Banská Štiavnica and Mr. Eigner visited this town several times as a diplomat. All of them were enchanted by the mysterious charm of this historical town, which is on the UNESCO Cultural Heritage list.

The historical novel about Maria Theresa, Adore the Queen, includes a large amount of historical life and institutions. The German reader is very attentive. After the first publication, I received responses from readers who brought small inaccuracies, from the German viewpoint, to my attention. Unfortunately, Mr. Gustav Just, the translator, is very old and does not translate anymore.

It would be good if young translators translating from Slovak took more interest in historical prose, which has presently become quite popular.

ANTON BALÁŽ: Besides presenting your own work, you often introduce contemporary Slovak literature at literary events abroad. What is the knowledge and perception of our literature in neighboring and other countries like? What kind of books and subjects have a good chance at reaching foreign readers (and publishers, firstly) in German-speaking countries? And, Michal Hvorecký was, as the only Slovak writer, successful with his novel Plush (Plyš), there. Which authors and books could potentially draw interest on the German book market?

ANTON HYKISCH: We must analyze the possible cross over of Slovak prose into the world based on the trends in readers’ interest. My visits of book fairs and bookstores abroad point to several spheres of literature, successful also from the marketing perspective.

Michal Hvorecký’s prose, which you mentioned, is a successful type of literature: a young author writing in the modern, reduced language of today’s young reader, a writer-celebrity, provocatively raising exciting questions about life. I must emphasize these value questions, especially. Slovak publishers incline to the opinion that wild stories about sex, excess and shenanigans are still interesting. But they are out of style everywhere else in the world. The young European reader wants more than Slovaks tend to think. In a more modest literary form, he wants the answers to serious questions concerning life. This can be seen from the interest in religion studies, mysticism, Oriental philosophies, etc. We might even find such books on the bookshelves of young Slovak authors.

Another favorite, opposite to this, is the search for a world which has nothing to do with the present. There is great interest in fantasy, sci-fi which delivers a kind of modern fairytale for adults. Everydayness wears us out, it is boring and so we are attracted to mystery, the past, and unfamiliar time periods. The Renaissance of historical novel, which is still underappreciated in Slovakia, has much to do with this. On its own, each generation wants to know about its roots and whether it was worth living a hundred, five hundred or a thousand years ago. Dusty old history textbooks have to be reinterpreted so that, again, we can discover their adventure and appeal. (Somebody is sleeping after a tiring journey. It seems as if took centuries. YOU ARE ALIVE, BECAUSE YOU EXISTED – these are the first sentences of the novel Time of the Masters.)

The third direction is a mixture of everydayness and mystery, reality and fiction. It appears as if classic fiction was losing its momentum. Not everything can be made up, the entire book cannot be a figment of the author’s imagination. People who lived through the two world wars and suffered under totalitarian regimes have discovered that reality surpasses the imaginations of 19th century writers. The stories of some real people are just more suspenseful. There is a worldwide boom of non-fiction (Word War II, fascism, communism, Che Guevara, etc.), especially among men. In the process of writing a novel, more and more facts, the mood of the era, citations from the media, family chronicles etc., get incorporated into the work besides the author’s fiction. It is a new kind of novel – a crossbreed of fiction and fact.

I think that my historical novels, too, have these features and that is why they arouse certain interest.

ANTON BALÁŽ: The visitors to the Slovak bookstand at the fair in Frankfurt had an opportunity to read an excerpt, in German, from your newest novel Remember the Tsar (Spomeň si na cára) which is a continuation of your line of successful historical novels. The central character is the Bulgarian monarch Ferdinand Coburg. Please briefly describe this book, focusing on its “Slovak dimension” and its integration into European history. How would you rate its potential success abroad – including Bulgaria?

ANTON HYKISCH: I’ve actually already answered that question. Remember the Tsar is not a classic novel about a little known European monarch Ferdinand Coburg. He was an educated man, a Catholic, he spoke many languages, he was a gourmand and esthete, naturalist and traveler, politician, he loved women, automobiles, locomotives, butterflies, and he was a bit of a bisexual. And a good friend of Slovakia. He spent almost every vacation in the Slovak mountains.

My book is not a traditional biographic novel. Among other things, it is also an exciting investigation within my family. My father (who died exactly 30 years ago) used to tell me about his eldest brother Anton. As a Slovak in Austria-Hungary at a time when Slovaks were not even acknowledged as a nation, this man reached the top. He became a private secretary of the Bulgarian tsar, the strange and mysterious Ferdinand Coburg. He traveled all over Europe with him. I inherited his photoalbum with unidentifiable photographs. The book of family memories opens and as an author I suddenly recollect that I had met the old Ferdinand when my father took me to a castle in Sv. Anton. I used to see him driving an off-road Mercedes to church in Banská Štiavnica every Sunday. And that’s how the image of the little known era before the year 1914 came about. What did our near ancestry do at that time? That’s a “Slovak” range of vision.

By crossing facts with fiction we get a novel about the complicated relationship between the monarch-politician and his servant, his secretary. It is about the relationship of political power and a simple young man. Politics versus everyday life.

This level also reveals a broad image of a small, independent Bulgaria in the web of European power politics. The reader is transported not only to Sophia, but also Vienna, Budapest, Berlin, St. Petersburg and Paris, and at the same time to the magical Slovak mountains with castles and forts, every summer. In addition, there is a conflict and a tragic conclusion in the trenches of the first atrocious war on the European continent. That is the universal, or more general dimension of this novel, and it could make it interesting for readers abroad.

ANTON BALÁŽ: In your books of essays and published texts, you often meditate on the standing of literature and culture in the world today. You talk about, and it is understandable, about their increased endangerment. How do you think we can overcome this?

ANTON HYKISCH: The modern writer must come to terms with some unpleasant facts. This, especially, applies to writers from post-communist countries.

The older writers, like me, have spent most of their lives “building socialism”. Literature and arts were of substantial importance there. There was no opposition allowed in a state with one ruling party. Artists, mainly writers, were the only esteemed critics of the regime at that time. Through their books they tried to present a true image of the reality and judged and criticized it this way. Writers, thus, substituted the non-existent opposition parties. They were popular and the public anticipated their every word, every new book.

Today we live in a democratic state and writers have all of a sudden become uninteresting, or even unnecessary, it seems. Writing and books are now mere products, just like cosmetic products, television sets, cars and dishwashers. Book prices have risen ten-fold, while the average number of copies printed have decreased ten-fold. This situation truly is disastrous.

As writers, we should realize that the world around us has changed. Reading books is no longer the only pastime. Our lifestyle has fundamentally changed with the arrival of new technologies. I grew up in an era when television did not exist. The radio (if a family owned one), was a treasured piece of furniture set in the center of the living room, dependant of an electric outlet. We had to go to the movies if we wanted to see a film. And so we read.

Today, most of our leisure time is dominated by audiovisual media. We’re slaves to TVs, cellular phones, computers and computer games. A young reader is often viewed as a nerd by those around him.

How do we overcome this? We have to push the book through in this fight. You cannot fall asleep with a computer laid out on your chest. With a book, you can.

Should we write books that one doesn’t fall asleep reading? Maybe. And if it happens, we should analyze the dreams of such sleep. We should investigate whether they are useful or help us and what they scare us off from. I don’t know.

We have to get used to the fact that reading is not a pastime of the masses. It’s more of a hobby of a certain group of people, entertainment and passion of a minority. We should acquaint ourselves with the things that entertain the majority. The solution, however, is not in stooping down to the level of reality TV shows. Books presume light, not darkness.

The only hope is what I had once called the “hope of the broken bowstring”. The hope that one day people will get fed up with the never-ending stupidity of the mass media. The bowstring of the infinitely stretched out foolishness will break and people, the masses, will start demanding something different.

Perhaps, that will be the time for us, writers. We will have to have loads of humanity, empathy, love, and simple dialog – dialog in silence and solitude- between two people, in store.

That will be the time of books, one of the greatest inventions, without which our civilization would not exist. Dogs and cats, no matter how cute, don’t read. Reading is an attribute of humanity.

Translated by Saskia Hudecová