DANA PODRACKÁ: Your collection of poems Fidelity (Vernosť) came out last year. You have my respect. “One who is unfaithful in small matters, will also be unfaithful in the great ones”. /Lk 16,10/ We encounter infidelity in great matters quite often; in politics and in relationships. Infidelity in small matters, however, is not so important to us. What are the smallest kinds of infidelity that actually count?

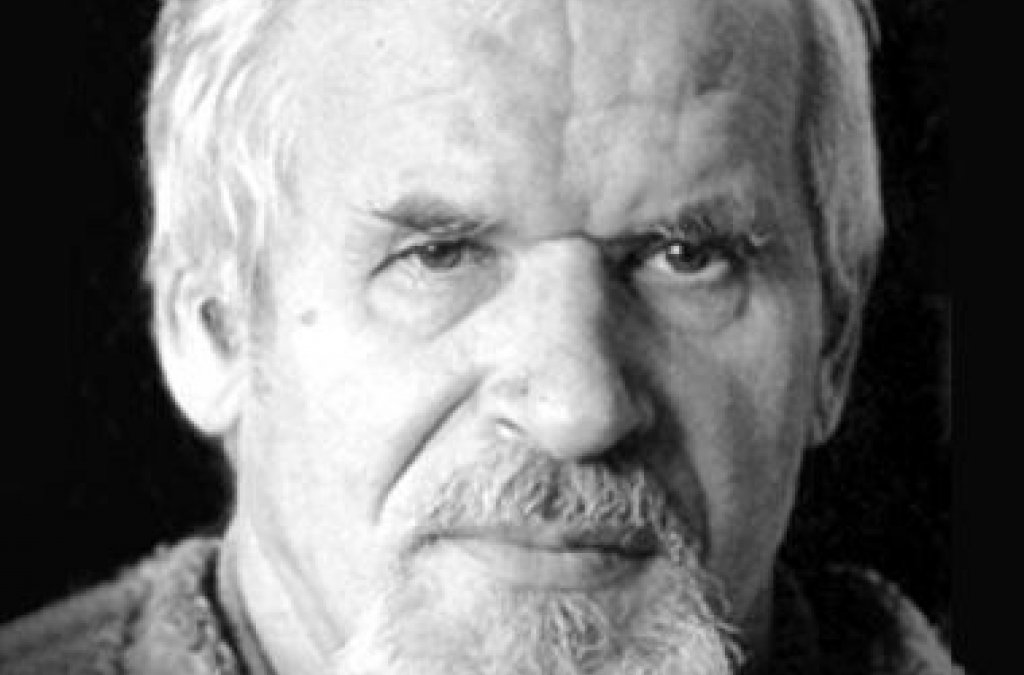

MILAN RÚFUS: I think it will be best if we start with – coming back; to the quote from Vladimír Holan – the quote which served as a base in my understanding of fidelity.

“And even though at times I had visions without revelations, I was so faithful that I became a witness.”

Holan defines poem as a kind of revelation in this passage. I can only attest to that. He comes to know art through intuition. A poem made solely from words reminds me of Potiphar’s wife who was left only with Joseph’s cape – Joseph himself, escaped her. Holan admits that he, too, sometimes created poetry only as an act of will. But he was so faithful to his desire for the secret that in the end he, at least, became its witness. And this is also a way to write a good poem. This Holan-esque passage surprised me in a strange way. As if the poet had said it for and to me. I accepted the principle of fidelity not only in connection with poetry but also in life. It has one flaw, though: fidelity to mistakes and the consequent fanaticism.

DANA PODRACKÁ: I consider you to be a mystic. What about you? Do feel the mystic inside you?

MILAN RÚFUS: I am a human being. In a very interesting book Denatured Animals, the French writer Vercors regards man’s need for myth to be the essential characteristic that separates humans from animals. And, again, I am a human being.

DANA PODRACKÁ: I read St. John of the Cross again, not so long ago. When reading certain parts I thought of you. I thought of your spiritual song, your climb on Mt. Carmel, your dark night, and your live fire of love. Saints resemble each other in their union with God. Is poem a sign of this union?

MILAN RÚFUS: Poem is a unification of man with the Secret and it calls this Secret different names. One of them is God.

DANA PODRACKÁ: You say: to be simple. Does not God, himself, use the words of simplicity and places them into a soul pure enough to accept them?

MILAN RÚFUS: God’s words are simple and effective. It is a language without words. The inviolability of the link between cause and consequence is the language of God’s righteousness, for instance.

DANA PODRACKÁ: Let’s go back to Fidelity (Vernosť). Three times Holan and the Bible once - as a motto. Do you have your own dark nights with Holan as he had with Hamlet?

MILAN RÚFUS: How did I come into contact with Holan and Czech poetry altogether? Sometimes even the ugliest hen lays a beautiful egg. I finished my studies at the Department of the Slovak language in 1952. Those were the peaking years of Stalinism. I was offered an assistant’s position in this department and I accepted it. However they made me secretary of the department. It was as it had been in guilds, when the youngest apprentice had to help the master’s wife wash diapers. Bureaucracy was the master at that time. Memo after memo. Plans were being set for the semester, for the year, for five years, even ten. I was desperate. Then I was saved by an offer of a two-year research stay for the study of Czech literature from the Ministry of Education. I took it immediately. I concentraded on Czech poetry which has always been better than their prose. That was it. And since I was born in the community of Lutherans in Northern Slovakia in times when they used the Bible of Kralice at mass, I was quite familiar with the language. Twice a year I was entitled to a study stay in Prague. If Hemingway had called his stays in Paris a moveable feast then Prague was such a feast for me. Failing to notice Holan was like failing to notice Mt. Gerlach in the High Tatras. But I never had the courage to stop by Kampa and ring his doorbell. I have never seen him in person but I can still sense him. There is also something else that links our lives. I have my Zuzanka and he had his Kateřina – a daughter with Down’s Syndrome. She lived for twenty-four years. This, too, is a part of my Holan-esque Fidelity.

DANA PODRACKÁ: I love this part from Holan: “I lived for man and his drama. There where a dual being is waiting and alone.” In post-modernism, the opinion that a poet is a multiple personality, started to appear. Is it so?

MILAN RÚFUS: A poet encompasses all human beings. Good and bad. Sometimes they bring him joy, sometimes sorrow, love or hatred. And within himself the poet has to pay for this hatred.

DANA PODRACKÁ: Does not the fact that Nietzsche’s prophecy: God is dead, is starting to fulfill, sadden you?

MILAN RÚFUS: I have always thought Nietzsche to be a bit harsh and it seems as if he took pleasure in this harshness. History was my minor in college. I was intrigued by the characteristics of societies in times when history decided to send them to the junkyard. The loss of myth was the first syndrome of their upcoming departure. And then there was the related hypertrophy of sex.

DANA PODRACKÁ: It is said that God loved the Jews the most because, out of all the nations, they felt His presence the most. It is an attribute of a mystic experience. Do you feel God’s presence sometimes? Like Pascal in his Night of Fire.

MILAN RÚFUS: I talk to Him as if He was my neighbor. Not just thank you and be praised. God is not conceited, wallowing in pleasure when praised. There are so many controversial things on Earth that it seems that they are its essence. And so I say to Him: “Did it have to be? Couldn’t it be any other way, Lord?”

DANA PODRACKÁ: What is your view on the new role of woman in the society?

MILAN RÚFUS: The patulent tree of Christianity planted into the Judaic base has its roots in the soil of the Near East and it has accepted its traditions in this matter. –Taceat mulier in ecclesia. Let the woman be quiet in an assembly.- I saw this in the Italian countryside near Naples. A man and a woman went to work in the field. He was walking first with a cigarette in his mouth, holding a stick. She went behind him hunched under the heavy sack of tools and food. My Italian colleague explained it this way: Here in the south a man can be idle all day long but he cannot loaf around at night.” What to do with this…? We have to forget it and move closer to humanity.

DANA PODRACKÁ: Could we say that your relationship to Zuzanka is Love, which hurts in order to bring love back?

MILAN RÚFUS: It could be described by these words. I will answer with a poem.

And Zuzanka, again

And again, it is here.

It is here again and anew.

Tell me, little girl,

are there words still,

which I have not said?

Are there such words of love,

withheld by your and my

difficult fate?

There are no more such words,

and will not be.

Because only love

can rebel against destiny.

With just its touch,

the bull inside softens.

And unpretty things

Will become pretty.

Translated by Saskia Hudecová